|

version française:

IV - 12.6 “We are tinkering with the incurable.” (Emil Cioran)

“The habit of misfortune. I press myself to laugh at everything, for fear of being obliged to cry about it.”

Beaumarchais,

The Barber of Seville, I, 2

(1775)

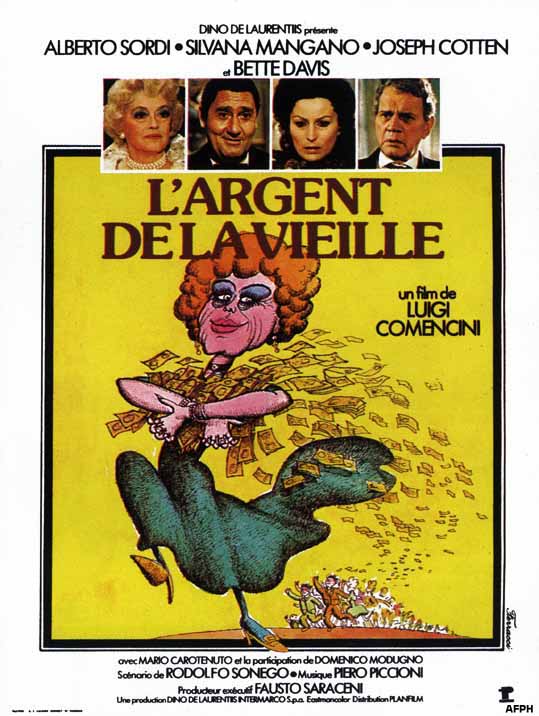

Laughter, the perversion of this polysemy that is particular to man, as opposed to all reason, proceeds from a vital illusion. “Health, happiness, blinkers. Illness makes everything finally lucid” (Roger Martin du Gard). This “infirmity”, to speak like Vico – that superb yet accursed philosopher who we would never have heard laugh: him who knows has no need for this absurd proof that laughter indicates – this infirmity life if “pessimism is reasonable and optimism is willing”, what we mean by that is this vitality that justifies the will to laugh or to not take ones adversity seriously, thus anaesthetising or blinding us with “knowledge” that reality contradicts. A Buddhist adage states that “hope is the greatest misfortune and dispair the greatest fortune.” But how can we stop hoping without leaving our human form? In Luigi Comenccini’s ‘l’Argent de la Vieille’ (Lo Scopone scientifico, 1972) an unfortunate couple has been trying for 8 years to win at a game against an elderly American lady which would make them rich into the millions… until the last part. “It’s death, says one of the characters, we can never win against that.” This is the reason of the granddaughter of the couple, the head of the family, who never smiles, never hopes, because she is infirm, and this vital importance makes her wise. She poisons the old lady and erases this reason to hope which is the reason behind misfortune. Will we ever win against the old lady? Certainly not. But we act like we will, by this folly that precedes and submits to any kind of reflection. Because life is about strength and not sense.

As a way of putting up with pain, laughter is equally a way of facing adversity. Anatole Chtcharanski who spent 9 years in a gulag said: “Humour is a weapon that allows man to resist inhuman conditions.” “Laughter! I can see the face that the civvies will pull when I say to them:’ I have never seen so much laughter than in a camp.” (Ana Novac, survivor of Ravensbruck in The golden days of my youth, 1957). In order to put up with a scene from a film which has been classified as ‘bloody’ – for example an amputation without anaesthesia – we sometimes see the spectator stocking up on insensitivity by giving a good old laugh. It is probable that if, for example, we had laid some volunteers in a coffin, the majority would take it as a joke. That which is serious is not only deadly by the boredom that it is reputed to engender: invited by an ethnologist to play dead for a scientific reconstruction of a burial, a native, without a doubt lacking in humour, did not survive. In effect, “Is there not some danger in feigning death?” Argan asks in the Hypochondriac (III, 1,1) “There are some days, we hear said, when so many catastrophes happen that we are obliged to laugh about them.” “What can one do, one asks the children of Beirut, when we are scared and we want to cry? – Well now, we try to laugh!” The only surviving castaway from a fishing boat that saw one after another of its five companions disappear, seized by the cold, recounts on television that he “made himself laugh so as to not sink”.

Be it recurrent - if you wish to see one of Feydeau's plays during the celebrations, (picture)

it is a good idea to reserve in advance, since you will not be the only one to want to pay yourself a slice of laughter to forget your worries and drive away the last year – or in one's temperament -“when we are always happy we are always happy”, this silly reasoning is empirically and chemically correct if euphoria is a breastplate that changes the perception of facts – laughter cancels out the damage and reestablishes integrity.

Othello – take quote directly from Shakespeare

But this truth is not evidently without absurdity

Othello – take quote directly from Shakespeare

We see the usefulness of pain for the one who lives in the world, as a warning of having to change what’s real or having to adapt to it.

In Norman Cousins experiment, taken from his work The Will to heal, laughter therapy – which was, furthermore, the cause of much research into the physiology of laughter – verifies, at least, the analgesic power of laughter. Cousins, then Editor-in-chief of the Saturday Review, struck down by spondylarthrite ankylosante, successfully began his own self-medication by laughter. Refusing the bleak medical prognosis that he was presented with, he decided to show funny films and stated that, whilst his illness was causing him unbearable sufferances, just ten minutes of laughter granted him two hours of peaceful sleep. He first related his story in the very official New England Journal of Medecine (reedited in The Saturday Review on 28 May 1977). Suffering, most likely, from the same illness, and reputed for his spirit as a humorist before the term had been coined (“I look like a Z. My arms are shortened as much as my legs and my fingers as much as my arms. I am a short cut of human misery”) was Paul Scarron (1610-1660), the inventor of the French Burlesque and author is Virgile travesty, Roman comique (and of this self-penned epitaph. “Celui qui ci maintenant dort / Fit plus de pitié que d'envie / Et souffrit mille fois la mort / Avant que de perdre la vie. / Passant, ne fais ici de bruit ! / Garde que ton pas ne l’éveille / Car voici la première nuit / Que le pauvre Scarron sommeille.”), and to whom we attribute this word from his deathbed “I will finally get better” the precedent in this “discovery” ?

Le Chemin du Marais au faubourg Saint-Germain

de

Paul Scarron

Parbleu bon ! je vais par les rues,

Mais je n’y vais pas de mon chef,

Ni de mes pieds, qui par méchef

Sont parties très malotrues :

Je marche sur pieds empruntés.

Ceux dont mes membres sont portés

Sont à deux puissants portes-chaises

Que je loue presque un écu.

Ah ! que les maroufles sont aises,

Au prix de moi qui suis toujours dessus le cul !

Non que s’asseoir sur le derrière

Soit laide situation ;

Car parmi toute nation

On s’assied en cette manière ;

Aussi ne dis-je que s’asseoir

Soit une chose laide à voir ;

Mais de dire qu’elle soit bonne,

C’est ce que je ne dirai point,

Avec la douleur que me donne

Mon derrière pointu qui n’a plus d’embonpoint.

Revenez mes fesses perdues,

Revenez me donner un cul,

En vous perdant, j’ai tout perdu.

Hélas, qu’êtes-vous devenues ?

Appui de mes membres perclus,

Cul que j’eus et que je n’ai plus ....

Laughing gas seems to have disappeared from joke shops, but one can still cite its use by the guru, of Indian origin, of a sect that founded a phalanstery, though today dissolved, in the North West of the US: suffering from chronic depression, his assistants sprinkled his throne with it, upon which he used to sit. We can also find cartridges of nitrous oxide, that are no longer used for medical purposes, on rave sites...

Continual laughter or excessive laughter seems probably to cancel out the benefit of laughing. The supposed sadness of comics does not evokes the characteristic depression of the state of lack. (Moreover, specific addictive behaviour exists amongst anaesthetists: Lutsky HM, Hopwood M, Abram SE, et al., 1993: 915-921) The negation of its naturalness, the tetany of laughing drives one towards death. “It is significant, notes the Mexican writer Octavio Paz, that a country as sad as ours has so many celebrations and celebrations that are joyful as that. For us, a celebration is an explosion. Death and Life, jubilation and lamentation, singing and shouting mix together in our public rejoicings. There is nothing more joyful than a Mexican celebration, but equally there is nothing as sad. The night of celebration is also a night of mourning.” (le Nouvel Observateur, 9 August 1985) But the night of mourning is sometimes also a night of celebration: for example when the funeral wake is lead by entertainers or on the occasion of story recitals, as we can observe in certain Creole societies (such as in Rodrigues or Reunion Island, for example).

... /...

|

|

|